Toolkit 2

Transition

You and Transition

Toolkit 2 aims to help you think about how relocation to a new country can affect you, the accompanying partner. It suggests some strategies and tips to navigate transition and a new culture. As you read Toolkit 2, we invite you to focus first on your own transition, while Toolkit 3 looks at the family.

Transition and adaptation work hand in hand whenever we experience change. Transition, according to Ruth Van Reken, is the internal process we go through as we navigate change. The “push and pull” of transition and adaptation come into sharp focus during relocation.

For example, if you feel “forced” to move, or you love your current location, the transition will be more challenging as you let go of what is dear to you. If you are looking forward to a change, then moving on to adaptation is much quicker and easier.

Everyone goes through a degree of culture shock whenever they move. Change is difficult for the psyche and can affect people in different ways. Understanding more about the phases of adaptation, culture shock, and the need to mourn hidden losses, will help you better process your transition.

Borrowing a Mop

A few days after arriving in Tanzania we moved into a temporary furnished apartment. On Monday morning my husband went to work and I took my daughter in a taxi to her new school. When I got back to the apartment I looked around. I knew no-one and had no internet or mobile phone. I didn’t know where I was in the city or where the shops were. What would I do all day? I started to feel very sorry for myself.

The maid arrived to clean. I had no cleaning supplies, and was on the verge of tears as she looked curiously at me. I decided I had little to lose by knocking on the door of the apartment below and asking to borrow a mop and bucket. At the worst, they would be rude to me or think I was stupid. The door was opened by a smiling Indian woman who laughed at my tale of woe and invited me in.

Meena loaned me all the cleaning supplies I needed and became my anchor during the first weeks. Through her I was introduced to the expat networks in town and got answers to all my questions. She and her husband became our good friends. Years later, after she had also left Tanzania, I asked her to help another WBG newcomer to Dar es Salaam. She introduced her by email to some friends, who helped her settle in. The connection flows on – and all because I dared to ask to borrow a mop!

Lunch Guests

It took some weeks in the Philippines before Inga felt confident enough to invite the wife of one of Johan’s colleagues to lunch. Corazon arrived more than an hour late, along with her sister and two of the sister’s children. Inga found herself embarrassed and confused. She didn’t have enough food at home for them all, so they went out to a restaurant instead.

Luckily Corazon had a good sense of humor, which relieved the tension and helped everyone relax. She became a good friend, and helped Inga learn about local customs and beliefs. Over time she came to understand that, for many people in the Philippines, relationships and the family group are more important than individuality. Also, concepts of time and deadlines could be different than what she was used to.

This helped her understand that the new dining table she had ordered might take longer than the promised six weeks. When she had insisted that she needed it in six weeks the shop-owner had agreed, because it would have been impolite to say no to her. Inga became more relaxed, as she grew to appreciate that most people were warmhearted and generous. She was very grateful for Corazon’s friendship, which made the local culture less mysterious to her.

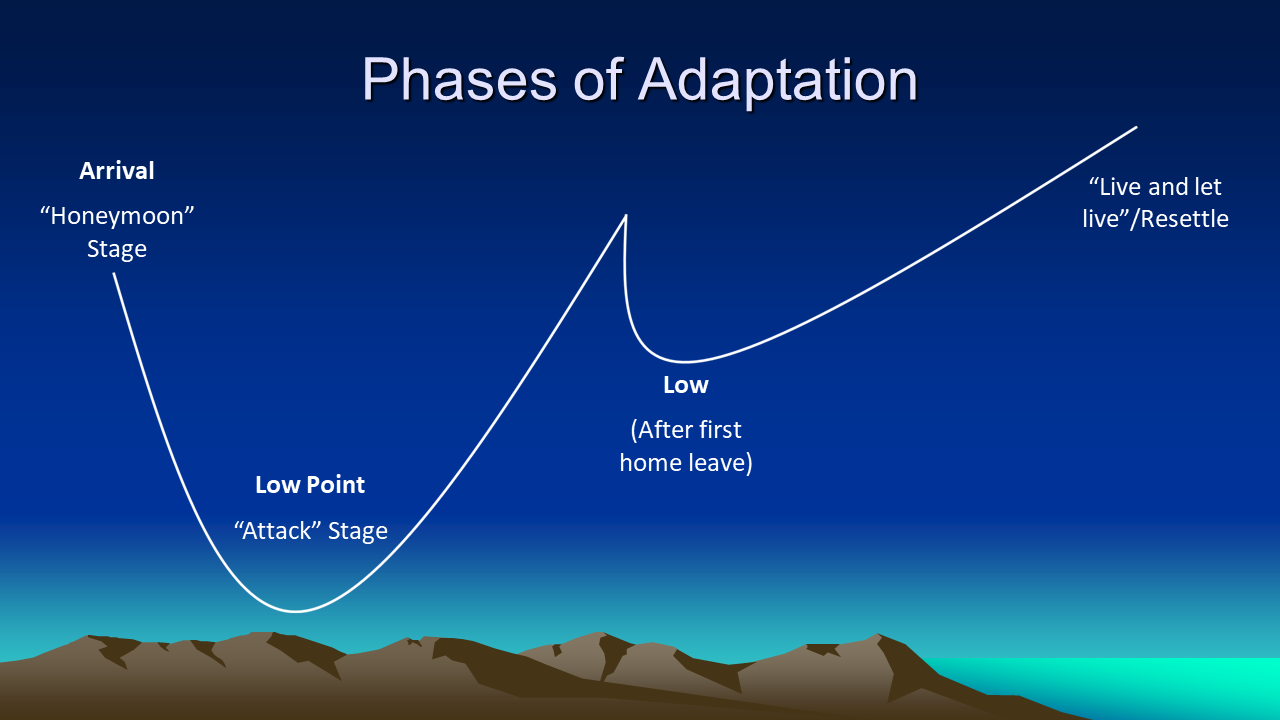

It can help to remember that adaptation is a phased experience. We all take time to adapt and we may oscillate between phases. Though the process of adaptation varies for each individual, there are some general patterns.

The model of adaptation and culture shock in the diagram below is based on the collective experience of our members over the years. There are three key stages. The length of time for each stage can vary, but it is important to recognize if someone seems “stuck” in the “attack” stage.

If there is a prolonged period of anxiety and stress it can be helpful to seek professional help. Warning signs might include changes in sleep patterns, drinking more alcohol, temper outbursts, excessive weeping, lack of motivation or frantic activity.

- The Honeymoon Stage: This is the stage of excitement on arrival and eagerness to learn about the new place. How long it lasts depends very much on:

- how well prepared you are for the move;

- how pleased you are about coming here; and

- whether there are unforeseen challenges in the early stages of settling in.

- The Attack Stage: Culture shock hits when you realize how many things are NOT the same. Even if you have moved many times, there will be an adaptation gap between the last location and the present location. The intensity of the culture shock depends on the degree of difference between this location and the last. This can cause feelings of uncertainty, loss of control and confusion. These feelings will pass as you begin to gain confidence that you know how to live in this new place.

- “Live and let live”/Resettle Stage: This stage comes when you have worked through the feelings of transition and begun to establish your life in the new place.As the diagram shows, you might experience a temporary “dip” when you return from your first vacation. Then the momentum of settling in will pick up again. You will know you have resettled when you start thinking of your new destination as “home.”

Your adaptation process can be affected by many factors:

- Personal temperament: Some of us embrace change and others are very reluctant and resist change. Knowing yourself can help you prepare.

- Lifecycle and experience: Moving is harder at certain life inflection points: for example, if you have recently had a bereavement or are moving soon after the birth of a baby, or you are leaving a sick parent. Also, previous traumas can make a person sensitive and vulnerable.

- Leaving children behind: The move can be harder if you have to leave children behind, perhaps at school or college, especially if this is the first time you have moved without them.

- The decision to move: Feeling “forced” to move can bring up emotions of anger and frustration. These can exacerbate the feelings of being trapped in an unwanted situation.

- Expectations: An overly idealistic picture of the place you have moved to can make you disappointed when you have to face the reality of daily life there.

- Previous relocations: Experience with previous relocations and other cultures can help. However, the accumulation of losses from repeated departures can sometimes make yet another relocation harder.

The role of an accompanying partner can be very challenging, especially when it is the first time. It can be even harder if you have given up your job for this relocation.

You might have heard the term “trailing spouse”, which was created in 1981 by The Wall Street Journal’s Mary Bralove. It captures the concept of sacrificing your career plans to follow your partner. There is also a concept termed “trailing spouse syndrome”, referred to in a study by Caroline Kjelsmark. She identified feelings of loneliness, a lack of direction, loss of identity, relationship problems, and a gap between expectation and reality.

It can be helpful to think of yourself, instead, as an “accompanying partner”, which is the term used throughout these Toolkits. A partner plays an important role in contributing to the success of the assignment. Being intentional about your adjustment can help you in making the most of your time in the new location, and in making the assignment successful for the whole family. (More on this in Toolkit 4.)

In the past it was taken for granted that the accompanying partner would be a woman, but now many men are taking this role. For anyone, leaving behind friends, family, defined roles and a regular structure of daily life can involve a sense of lost identity.

It takes time to adapt and adjust, get a new home ready, make friends and find your way around. During this time you might feel disoriented and lost, and miss what you left behind. Most people say that it can take up to a year to settle down in the new place.

It is generally the accompanying partner whose role at home, in the relationship, and in the community changes most dramatically after relocation. School and office provide other family members with structure to their day and people to interact with. You have to create your own time structure and support system, and might be alone for long hours at a time. Maybe you have small children to care for, but no adult company.

Also, it is often the accompanying partner who encounters the new culture most directly. For example, you will probably have to interact with shop assistants, workmen and service providers, and maybe household help. This can be both baffling and frustrating, depending on where you are in the adaptation cycle.

However excited you are about the new country the honeymoon can be over quite quickly. Soon the upheaval and the loss of a familiar environment can throw you off-balance for a while. Often things don’t work out as you anticipated. Everything you knew about how to navigate daily life and run a home may seem irrelevant here.

You may become more dependent on the WBG staff member partner, who at the same time may be preoccupied, or even away on mission. It can be difficult for each partner to understand the experience of the other, and there can be frustration and anger on both sides.

For the staff member, adjusting to a new work environment, with high pressure to perform well, can be very demanding. This can affect the emotional energy available to be caring and understanding at home. As noted by relocation expert Robin Pascoe, they can also be carrying a burden of responsibility for uprooting the family, which can affect mood.

This section, and the related strategies below, are derived from a tip sheet written by Ruth Van Reken for these Toolkits. (See “Transition Tips” in More Resources)

You will find the concept of “hidden losses” woven into most of these Toolkits. This is because the journey of expatriation is about gains and losses. Globally mobile families who understand the normal transition process can find strategies to cope in healthy ways with this experience.

In order to allow yourself to process the losses of transition in a healthy way, it is important to understand that:

- It is normal to miss someone or something you love when you don’t have them anymore. That is what grief is.

- Grief is not a negative. We try to avoid feeling it because in the moment it is not a pleasant feeling. The truth is that the more we have loved someone or something, the more grief we will feel. Oddly, grief is an affirmation of the good!

- The losses of international mobility are often hidden, unlike an obvious loss everyone can see, such as a relative dying. We can even feel a sense of loss when the next place is a dream job or location.

- If we ourselves do not recognize the losses, or minimize them, the grief remains unresolved. One psychologist aptly calls this “frozen tears”.

Ruth Van Reken, expert on Third Culture Kids, describes a hidden loss as “a loss that is often so nestled within the good of the experience that it isn’t even visible.” Hidden losses also recur with each move.

Types of hidden losses include:

- Loss of lifestyle

- Loss of status/identity

- Loss of dreams

- Loss of possessions

- Loss of relationships

- Loss of the world that was

If grief is normal for all losses, why is it that in our globally nomadic world many people struggle with unresolved grief, the aftermath of losses we have never dealt with in a healthy way?

One of the biggest reasons for grief being unresolved is simply a lack of awareness of what we have experienced. This is why it is important to take time to identify and acknowledge what we have lost. There are the obvious things, like house or relationships, but ask yourself what it might be in that thing that is more hidden.

Perhaps, in terms of relationships, it can be something as simple as, “No one in this new place knows my history. There is no one to whom I can say, ‘Do you remember when…?’, and they remember. I have to retell my story from scratch every time.” Or, if you have children who are not with you, “No one in this new place knows my children.”

Another very real loss is that of identity. This comes from leaving behind a particular lifestyle and sense of status or place in a certain community. Perhaps you have left behind a dream of what you were going to accomplish in your former place, and this move has stopped that from happening. Or, you dreamed of how life would be in the new place, like Maud in our story in Toolkit 1, and now you see that the reality is not like that.

The problem for most of us is that because there is often so much good to focus on, we try to ignore the losses and grief. We try to think about all the good and hope that the sadness, depression, or quick anger will fade away with time. Yet, no matter how much we have gained, if we don’t face what we have lost those symptoms will continue to rear their ugly heads in unexpected ways and places.

Another reason that grief can remain unresolved is because we do not have, or give others, permission to address the losses. The accompanying partner is often given a list of reasons for the move – duty, service, financial gain – and the individual feels, “How can I compete with that?” But understanding a reason for the loss does not take care of our need to mourn. Too often it means we just suppress it.

Time is another factor. Long ago, people moved between continents by ship. Now, that same trip is only a few hours in the making. A world dies with an airplane ride, but there is no funeral. Before we have processed the goodbyes we are thrust into the chaos of the new hellos and all that we have to learn. In a real funeral, we first express our sympathy and spend time with those in grief before we try to make plans for the future.

The truth is that with any transition there is always loss, no matter how much good will be gained through the change. Loss always creates grief, whether we consciously know it or not, and grief will be expressed in one way or another. Denial, anger, or sadness are the most common ways. Trying to pull down a curtain on the past can lead to being caught in a pattern of overwhelming sadness and unexplainable bursts of anger.

Without healthy processing of our losses, each move adds more unresolved grief to the secret closet inside our hearts where we have tried to store these things. We might use different behaviors to try to patch up the cracks where some feelings want to ooze out – internet addiction, texting, drinking, gossiping, gambling, online games, busyness, and so on. But underneath those coping mechanisms there is still a gnawing feeling of sadness or anger.

The key thing then, with the hidden losses of transition, is to name them, grieve and then rebuild. We will get through them, but to do so in a healthy way we need awareness, permission, time and comforting. Healthy mourning takes time. It is fine to give some space for it all. (See more in Strategies and Tips below)

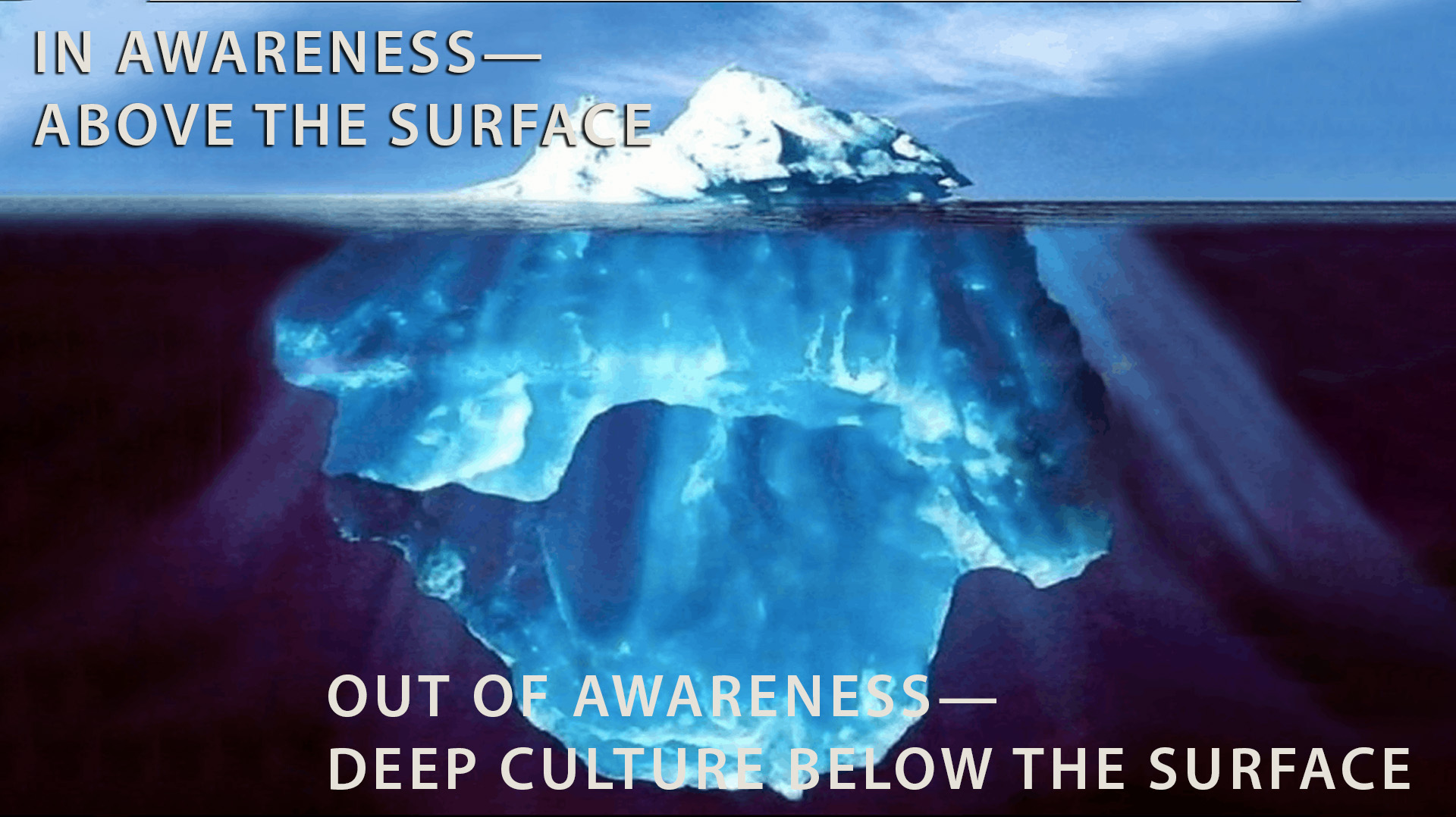

Navigating cultural differences is another important aspect of transition. Each cultural group has its own frame of reference, consisting of a coherent pattern of beliefs, feelings and behaviors.

The Iceberg Model is often used when seeking to understand cultural differences. The smaller part of the iceberg, which is above water, represents those aspects of culture that people are aware of, such as how we greet each other.

The larger part of the iceberg represents deep culture, which is hidden below the surface of conscious awareness. Deep culture is made up of feelings, thoughts and behaviors, which you might never have thought about because they are so familiar that they are part of you.

When we move to a different country, we are generally aware that we might encounter different language, habits and customs. However, we might not realize the potential impact of deeper cultural differences, involving inherent cultural beliefs and values. It is as if two icebergs come too close and the underwater parts crash into each other. We call this a culture clash. A sure sign of a clash is when one or both parties feel uncomfortable and off-balance.

Perceptual acuity refers to the meaning we see in another person’s behavior. It determines how we interpret their actions and how we respond. Culture clashes occur when we misinterpret intention, based on our own cultural experience. For example, in our story, Corazon did not intend to be rude when she arrived for lunch with additional guests, but was sharing the warmth of her family with a lonely newcomer.

If we avoid the discomforts of such clashes, or hide them away without thinking about them, we don’t learn anything. We have opportunities to increase our perceptual acuity of the host culture and develop our intercultural competence if we can tolerate the clash, experience our feelings, and reflect on the process.

The continuum of intercultural competence, below, is adapted from the Intercultural Development Continuum, developed by Intercultural Development Inventory (IDI) LLC, on the basis of Milton J. Bennett’s Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity (DMIS).

Continuum of Intercultural Competence

MONOCULTURAL MINDSET

Misinterprets differences

DENIAL

When you arrive in a new country, you might be completely unaware of differences, and misinterpret situations. For example, if your driver laughs after banging the car, you might think he is taking it lightly. You don’t know that, in his culture, laughter can cover up uneasiness, or even fear.

polarization

Judges differences

De-emphasizes differences

Minimization

Later you might tend to underestimate the importance of certain differences.

Once you start to settle down, you develop a deeper appreciation and understanding of the culture and learn how to avoid the pitfalls.

Acceptance

Deeply comprehends differences

Bridges across differences

Adaptation

At the final step, sometimes you adapt and actually make some of the cultural values your own.

Intercultural MINDSET

MONOCULTURAL MINDSET

Denial

Misinterprets differences

When you arrive in a new country, you might be completely unaware of differences, and misinterpret situations. For example, if your driver laughs after banging the car, you might think he is taking it lightly. You don’t know that, in his culture, laughter can cover up uneasiness, or even fear.

polarization

Judges differences

Minimization

De-emphasizes differences

Later you might tend to underestimate the importance of certain differences.

Acceptance

Deeply comprehends differences

Once you start to settle down, you develop a deeper appreciation and understanding of the culture and learn how to avoid the pitfalls.

Adaptation

Bridges across differences

At the final step, sometimes you adapt and actually make some of the cultural values your own.

Intercultural MINDSET

- “Unpack your bags and plant your trees”: This advice was given by Rev. Charles Frame Sr. (father of Ruth van Reken) to his fellow expats arriving in Liberia. Unpacking familiar items and photographs can give a sense of familiarity and continuity, even in temporary accommodation.

- Get an Internet connection: This will be one of your first priorities. Use it to stay in touch with loved ones and join online activities, such as the WBGFN global programs. Be aware that spending too much time online can prevent you finding connections and activities in your new location.

- Meet people: Be proactive in reaching out to people, even if you feel uncomfortable at first. Make a habit of noting contact details of people you meet, and make plans to meet up with them again.

- Build new friendships: Join different groups, expat and local. You might find new friends in unexpected places. The local WBG Family Network group can be a good place to start, to create a support network.

- Reflect: Ask yourself what worked well for you in previous relocations, or life changes, and what didn’t. Intentionally stop doing what didn’t work before. (More on this in Toolkit 4)

- Look around you: Each day consciously identify something to enjoy or appreciate about your new location. Note them down and look back at them when feeling negative.

- Take the next step: ask yourself, “What is the one “next thing” I can do”, even if you can’t do everything. This will help you when you feel totally lost and don’t know how to move on. Taking control of one thing will make you will feel less like a victim, and help you believe that there is still hope for good to come; and it will come!

- Remember that adaptation has phases: Be patient with yourself and your family members. At the same time, be aware of potential warning signs that might signal the need to seek professional help. Our Family Counselling Service (FCS) provides free, professional counseling.

Ruth Reken suggests these 4-step strategies for dealing constructively with losses in our lives, hidden as well as overt, so they do not haunt us for a long time.

Name what you have lost: Find a quiet place and ask yourself, “What did I lose in this move?” What might it be in each thing that is a hidden loss? Once you have identified the hidden losses you can honor them as real. Expressions of honoring a loss might include writing about it, or writing to someone in the previous place. Looking at photos of the place or people can be helpful in this period.

Acknowledge the losses: We need to comfort ourselves and others before we try to encourage. When we give comfort, we acknowledge the loss and stand with another person in it. Ironically, giving encouragement too soon is another way that we take away permission to grieve. We try to push someone ahead too fast, or emphasize the good that will come, before acknowledging the loss.

Allow the grief: Give yourself and others permission to feel and work with each loss. Don’t try to talk yourself out of the grief. Don’t minimize the loss by comparing yourself with others who seem to have lost more. Remember the importance of living in paradox: we can be glad for all the good, and at the same time miss all the things and people we have loved and lost.

Be patient: Remember there is a time factor in mourning. When someone dies, we understand that time is needed for the loved ones to process that loss. Have patience with yourself and others in the process of mourning your relocation losses. Grief can come in surprising ways and times, even weeks and months later. When it comes, tears may be appropriate. Don’t feel shame or blame if you find yourself missing the past for a bit longer than you expected. That can be normal, and you will get through it.

Adapt the dreams: After this process of grieving, consider if there might be different ways to do the things you are missing, or new things you can do instead. Is there a way to adapt your dream to fulfill it, even in a slightly permutated form? (See Toolkit 4, on making the most of your assignment)

Learn the language: Try to learn something of the language and culture. This can help bring back a sense of control and certainty in an unfamiliar situation. Joining a language class can also be a way to learn about the culture and meet new friends.

Make local friends: A local friend, especially one who has lived overseas themselves, can be an invaluable “culture guide”, like Corazon in our member’s story.

Reserve judgement: Try not to form opinions too quickly. Do not just accept other people’s interpretations of the culture and behavior of people in the new country. Be prepared for your ideas and interpretations to change as you live there longer and meet more people.

Learn from experience: If you experience a culture clash, it can be useful to think about it and reflect on your feelings. Remember that the other person was simply doing what they were used to. Though the behavior might not make sense to you, it could be normal to the other person.

Try to understand: One way to deal with a culture clash is to discuss it with a host country national friend, or someone who has lived there for a while. Tell them what happened, what you said or did, and what the reaction was. Try to see what you might be missing or not understanding.

See the funny side: Having a sense of humor can also help, as in Inga’s story. But take care that others don’t think you are laughing at them and their culture.

Here is a useful exercise to help you identify and name your losses, as well as rebuild your new social network, with more precision. For another useful exercise on transition, see Toolkit 5. Social Support System

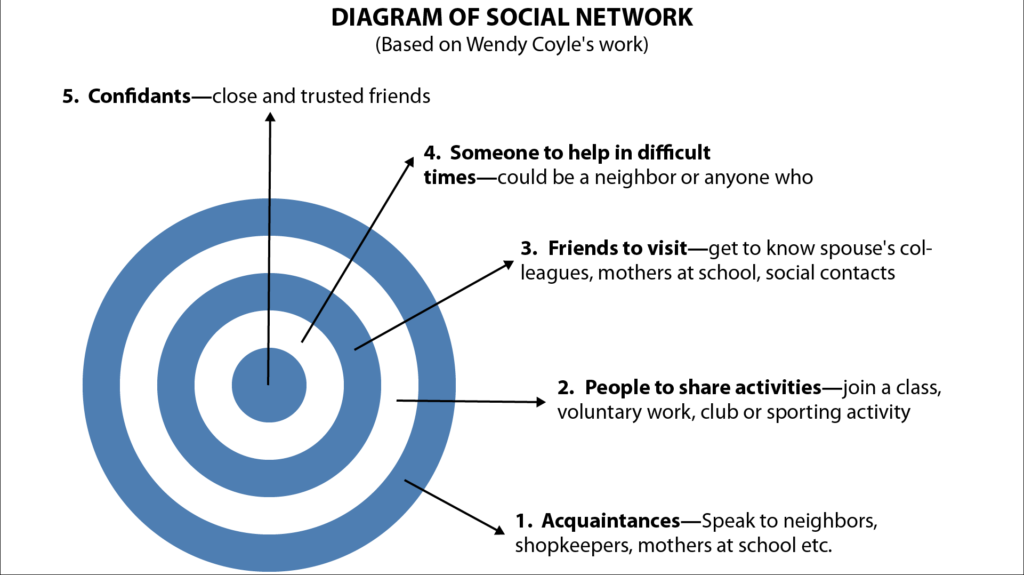

This exercise can help you understand your social networking needs, and kickstart your adjustment by building a new social support system. Research by Wendy Coyle, author of International Relocation: A Global Perspective, has shown that the number and quality of your friendships and activities prior to moving is an indicator of the degree of loss to be expected with the move. If you are feeling negative about changes after the move, it can be because of the decrease in your level of social support from what you are used to, rather than from the actual size of the new network.

Make a copy of this diagram. In each of the circles, using a red pen, write the names of the people in that category you have left behind. Using a green pen, write the names of people who moved with you, or that you have met since your move. You need to work towards getting some names in green into each circle.