Toolkit 5

Re-entry

Re-Entry Shock

The aim of Toolkit 5 is to help you think about what happens when you return to your “home country”, or a place you call “home”, after being away for an extended period of time. This could be the country you were recruited from or where you have chosen to settle down, or perhaps your return is to Washington, DC after an overseas assignment. Many experts suggest, and anecdotal evidence shows, that re-entry is often the most difficult part of the international assignment cycle.

Re-entry can be for a variety of reasons, such as end of contract, retirement, or personal reasons, and can be voluntary or involuntary, planned or sudden. Whatever the case, you are likely to experience what has been termed “re-entry shock.” Another term often used is “reverse culture shock”.

Neither you, nor the place you return to, are the same as when you left. At the same time, you will be missing what you have left behind in your previous location. Just as in other relocations, on re-entry, it is necessary to acknowledge our losses and grieve them, in order to make new beginnings.

Another Foreign Country

We disembarked from the plane in August 2020, full of hope for the coming years in our “home” country of America. We had been planning this move for years. Although we acknowledged that we would experience culture shock we weren’t quite sure what form it would take, and underneath it all perhaps we believed it really might not be so hard.

How difficult could it be to return to your home country? Secretly, I worried most about cleaning my house without help and finding a noodle shop for our favorite ginger beef. Like all culture shock, however, reverse culture shock hits us at times and in places and ways we rarely imagine.

Lillian Hellman said it well: “People change and forget to tell each other.” Old friendships we hoped to rekindle with ease have taken time and adjustment, as we and our friends realize how much we have changed. We are so grateful to have a handful of WBG friends where we can relax and share the joys and frustrations of “coming home.”

We experienced the pain of realizing the school we chose was too small and lacked diversity. After years of diverse international classrooms, our two mixed race teens often felt out of place and misunderstood. They were saddened when racially insensitive “jokes’ (even though not directed at them) were bantered around the classroom.

So, this year they have changed schools again, going for the first time to the local public high school. Years ago we had learned, with our oldest child, that the IB diploma is often set up quite differently in America than overseas. This time we remembered – yes, our students will still have to take U.S. History and Government.

For me, after years of being a full time “trailblazing spouse”, I re-entered the workforce here in America with a few fits and starts. With each country move I had to carve out a new identity, but this was perhaps the hardest – figuring out what I wanted to do with “the rest of my life”.

With all the adjustments, we often felt like we were living in an “alternate universe”. I coined the phrase, “Pretend like you are in another foreign country and give yourself time to learn all the rules and norms of this strange land.” Yes, even if it is the country you call “home”.

Living with Uncertainty

In March 2020, our fourth year in Cameroon, we got a call to come home urgently to France because my mother-in-law was seriously ill. We packed clothes for one week, and left with our two children, aged 10 and 12. After two days in France, Covid-19 lockdown started. This was our first adaptation to an unknown situation, shut in an apartment with my in-laws, while my wife worked online. This new situation took collaboration, imagination, compassion, and great willingness to adapt.

After a week of confinement came the second adaptation to an unknown situation – we learned that the school in Cameroon would continue online until the end of the school year, and by then my wife’s contract would finish. It didn’t make sense to go back there in Covid. We had to explain to the children that there would be no return to school, no farewell party, no goodbyes to home and friends. There will always be something missing because of our unexpected, rushed departure, which did not allow us to say our goodbyes.

By the time the lockdown ended my mother-in-law had unfortunately died. We consulted a psychologist to talk about bereavement and grieving losses. For the children it was the first experience of losing a family member. At the same time, they were mourning the loss of their friends, home, school and environment. During the summer I participated in the virtual meetings organized by WBGFN on The Power of Relationships, with a psychologist who offered us solutions, and I understood the importance of being helped by a professional.

Our Cameroon episode was over, a bit quickly without really closing the chapter, but a new chapter was opening as my wife had a position in Pakistan. Organizing our move in our absence was another new, unforeseen and stressful situation. Nothing had been prepared, sorted, or organized. The move got done thanks to technology and the screens which have taken an almost permanent place in our new life. We decided to stay in France until school re-opened in Islamabad. This meant that we had to find an IB school and a house, and adapt to another new, temporary, way of life in our home country.

We finally left for Pakistan after 11 months, 4 houses, 4 lockdowns, bereavement, an online move, online work and school, Covid stress, and not knowing how tomorrow would be. We learned that in new, unknown, and unthinkable situations, you have to be able to change your vision of the future and live in the short term – fifteen days, one month. A week after we arrived in Islamabad the school there went online again, but we were ready and adaptable!

Often, we arrive at a new place filled with mixed emotions. We are sad to leave our previous location yet excited about what is to come. Except this time we have arrived “home”, or a place that has previously felt like home, and we think the transition will be easier. However, research and lived experience indicate that more than 60% of repatriates find re-entry shock, the shock associated with returning home, equal to or greater than the culture shock on a new assignment.

Workplace health specialist Rensia Melles has noted that, “Leaving a foreign assignment behind presents the expatriate with three tasks: closure, reintegration, and definition of a future.” This applies whether you move on to another assignment or return “home”.

Successful closure starts in the previous location itself, with the process of “leaving well”, discussed in Toolkit 1. It entails the healthy grieving of hidden losses, discussed in Toolkits 2 and 3. Sometimes, in the excitement of returning home, what we have left behind and lost gets overlooked, or we can feel like we are almost betraying our home country by grieving our life elsewhere. Our very success in establishing a meaningful life in our assignments makes it all the harder to give up that life. It is necessary to take time to grieve before facing the demands of reintegration and building the future.

Reintegration into our home country can be unexpectedly challenging. Planned, voluntary returns are in many ways like moving on to a new location, except that when we return to a place that we are familiar with we don’t expect to feel any culture shock. It does come as a rude surprise when you don’t feel “at home” at home.

American author Marilyn Gardner was raised in Pakistan and went on to raise her own children in Pakistan and Egypt. In her blog, she writes, “Moving to the United States proved to be the most difficult move I have ever made. For a long time, my cross-cultural and international roots remained silent as I struggled to connect and fit into my passport country.”

You may have left as a young professional and now you are returning at a different stage of life. Maybe now you are a mid-career professional, or a homemaker with children, or a retiree. The place feels familiar and yet, somehow, it’s not. You find it hard to connect with old friends that you used to have so much in common with. This is how seasoned expat writer Robin Pascoe describes it: “You feel like you are wearing contact lenses in the wrong eyes. Everything looks almost right.”

Craig Storti, in his book The Art of Returning Home, lists the following variables that can affect re-entry stress.

- Voluntary versus involuntary: Involuntary is more stressful.

- Age and stage in life: This can add to or lessen re-entry stress.

- Previous re-entry experience: Like your first move, the first re-entry is the worst.

- Length of stay overseas: You may have got used to or loved the expatriate way of life, and be sad to leave it and come home.

- Degree of involvement in previous locations: The more involved you became in the previous place, the harder it may be to leave it behind.

- The re-entry environment: The more familiar and supportive, the easier the re-entry. Do you have old friends to return to? Are family excited about your returning home? Is it “home” for both partners? For your children?

- Amount of interaction with the home culture while you were away: Are you familiar with the changes at home since you last lived there? Sometimes, the country could have changed so much that it doesn’t feel like home anymore.

- Degree of difference between the kind of life you had overseas and will have at home: This also includes cultural differences. For example, if you are used to household help and a driver, returning to DC could be quite an adjustment.

As mentioned in previous toolkits, the response to moving and transition is a unique personal experience for each person, though triggers are similar. One difficult challenge faced by children on re-entry is often that of being the “hidden immigrant”. This is the term used by Norma McCaig and David Pollock to describe the experience of Third Culture Kids (TCKs) returning to their passport culture. (Read about TCKs in Toolkit 3, and More Resources.)

Maybe your children joined your family while you were overseas, or they left the home country as babies or small children and are now returning as teens or young adults. For them the experience might not feel like re-entering, but entering for the first time, even if they visited for holidays. The cultural dissonance and how “different” they may feel depends on many factors, including where they have lived before this homecoming.

Even if your TCKs seem outwardly the same as others at school, they will think and act differently. True, the digital world is a great equalizer, in that young people are sharing the same games, music, influencers, etc., all over the world. Yet, there is still a difference between TCKs and their peers because of their cross-cultural childhoods. This can be difficult when others expect them to be just like kids who have lived in the same place all their lives.

They may be expecting to fit in, but perhaps nothing in their experience has prepared them to do so. They may not be socially equipped for life in the home country. For example, they may have used other languages at their old school, and now feel less comfortable in the “home” language. Classmates here may talk about events they don’t know about, and share “in-jokes” and jargon they don’t “get”.

If you are returning to the Washington, DC area, you might be surprised if your children have difficulty adjusting to life in a big public school, after being in international schools or different school systems. They might not understand the expectations of teachers and students, as in our story in Toolkit 3, and might not readily fit into any group.

Another typical challenge is that the legal ages for driving and for drinking alcohol may be different from where you lived before. In the DC area, the minimum age for driving is 16, so your teenager may feel the odd one out returning at 17 and unable to drive. They might have been used to drinking socially in a country where the legal age for drinking is 18, whereas in DC it is 21.

It is very important to acknowledge what your children are experiencing in re-entry and to recognize that, like you, they need to grieve the life they have left behind. Kathleen Gilbert, who has researched grief among TCKs, has noted that losses not successfully resolved in childhood have an increased likelihood of recurring in adulthood.

She writes, “For TCKs, questions about who they are, what they are, where they are from, what and who they can trust are examples of existential losses with which they must cope. And the way in which they process these losses will change, or may even wait until long after their childhood.”

Unplanned and involuntary moves back home are even more challenging, particularly in times of crisis. The crisis could be a personal one, such as the death of a family member or a health issue, or work-related, such as unexpected redundancy or non-renewal of contract. Or it could be a political crisis, or a physical or humanitarian disaster in the country where you were located.

During the COVID-19 pandemic some WBG families found themselves stranded “at home” between postings, when they went home for leave and could not return to their duty station. Some, like the French family in our story, had to move on to their new assignment without having closure in the previous one, or even packing their own household goods.

In such situations you are totally unprepared and taken by surprise. Amidst such high levels of uncertainty, it is very important to try to regain some control over the small things you can control. For example, try to establish a daily routine for yourself and your family. There is much unfinished business, so allow yourselves time to process the losses.

An involuntary move is even more complicated if it results from a loss of job or demotion. The formerly working spouse, in particular, will be experiencing a myriad of emotions. These can include guilt, anger, shame, and fear about the future, in addition to having to explain to friends and family about the early return.

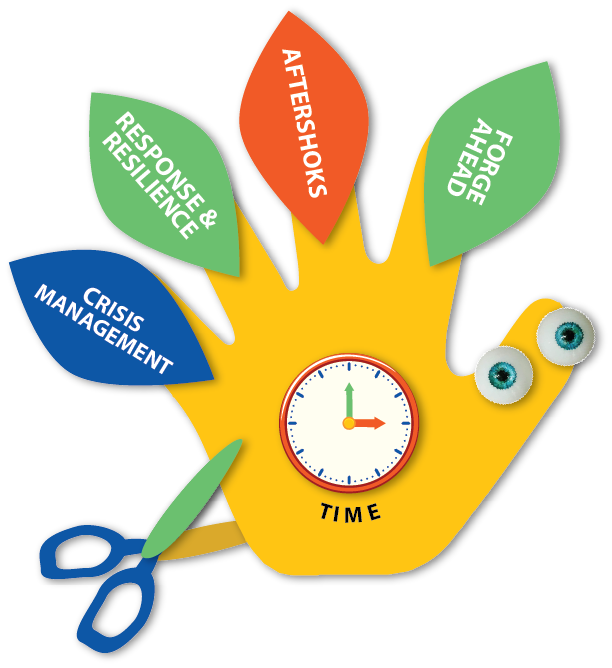

In Toolkit 1 we discussed the building of a RAFT for a planned departure. Marilyn Gardner, in her blog, Uprooted with no RAFT, notes that a “Crisis before the RAFT changes everything”. A different tool is needed for unexpected departures, virtual goodbyes, and long periods of waiting in between. She uses the acronym CRAFT to help navigate this difficult passage of life.

The suggestions given below are intended to stimulate your thinking and give you some ideas. They include advice from TCK expert Ruth Van Reken in “Transition Tips”, written for the WBG Family Network, and from Marilyn Gardner’s blog, “Uprooted with No RAFT”. (See More Resources)

Use your skills: To settle back “home”, it can be helpful to use all the skills that you have developed through your relocation transitions, and that we have discussed in the previous toolkits. This is the resilience referred to in the CRAFT model.

View it as a new place: Being in discovery mode about “your new home” is an incredibly useful mindset to adopt. Be alert to ways in which life and people, including yourself, might have changed since you left, and be open to getting to know a “new place” and situation.

Find others who understand: Chronic cycles of separation and loss are hard even when we are used to them. Knowing that someone else understands is often the first step to healing. Seek out people who understand and can offer comfort, even if it is online. WBG Family Network has many members who have shared this experience and will be happy to listen, even after your staff member has left the WBG.

Learn what to expect: If you are planning re-entry due to retirement, try to attend a pre-retirement seminar organized by Human Resources. These can be very helpful in managing your expectations. If you are returning to DC, attend an online WBG Family Network Welcoming session.

Acknowledge the losses: Revisit the strategies and tips for processing hidden losses, suggested in Toolkit 2, and give yourself time and permission to honor these losses, as in any previous move. Ruth Van Reken advises, “Listen to life”. If you find yourself reacting with depression or bursts of anger out of proportion to an event, recognize that sadness and anger are both stages of grief.

Look after yourself: Do not neglect your own self-care. Remember that on a plane you are told to put on your own oxygen mask first, before you can help anyone else.

Get help: Do not delay seeking professional help if you think you or another family member could benefit. A chat with one of our Family Consultation Services (FCS) counselors could be a good place to start.

- Talk with your children: Marilyn Gardner advises, when in a crisis gather your kids to you and talk about what is happening. She points out that if you ask adult TCKs what made the difference in making it through a crisis and building resilience, many will say that it was that their parents and other adults in their lives allowed them to talk about what was going on.

- Grieve the losses: As with previous relocations, allow your children and teens to acknowledge and grieve their losses, and avoid judging them for not feeling immediately “at home”. It might feel more like “home” to you than it does to them. Keep in mind that grief might present itself as anger or behavioral issues, as discussed in Toolkit 3.

- Honor the previous place: Perhaps make a collage or picture album of the places you visited and loved during the last assignment. Some teens might like to wear sweatshirt with their former school’s insignia on it, so they can proudly declare this connection to others.

- Research TCKs: Explore the research on Third Culture Kids (TCKs) returning to their passport culture, and share what you learn with your children, as appropriate to their level of understanding. Encourage older children and teens to do their own research to give them a sense of owning this experience.

- Normalize the experience: Encourage your children to find ways to connect with others with similar international experience, such as by joining school international clubs or online groups for TCKs. Normalizing the experience can make it more manageable. WBG Family Network organizes programs for teens from time to time, including online programs.

- Focus on first things first: Apply Marilyn Gardner’s CRAFT model suggestions to your own experience. When in crisis, she advises to focus initially just on the physical needs: “The emotional pieces will come, but you don’t have the energy, nor should you focus on them right now. Responding appropriately to the immediate issue builds resilience for later in the crisis.”

- Watch out for “aftershocks”: She also advises to remain on the alert for “aftershocks”, which will probably come, like after an earthquake. Aftershocks from a crisis can be as difficult emotionally as the crisis itself. They come unexpectedly, and set off previously felt trauma and feelings of shock and helplessness once again.

- Do what needs doing: The acute phase of a crisis is followed by the maintenance phase. You and your family need some stability, even if it is temporary, as for the French family in our story. Ask yourself, “What is the new routine? What can we put off, and what needs to be done today?”

- Ask for help: As in any new location, keep track of contacts and resources who might be able to help you, and don’t be afraid to ask for help. List the WBG Family Network as one of your resources, and contact us.

- Say goodbye remotely: If you had to leave your previous location without time to say proper goodbyes, think about if there is there a way to do it retrospectively. Whether through a video call or email, or by sending gifts, find a way to say, “Thank you for who you were in my life while I was there”.

- Plan for closure: Perhaps you can plan to go back, when circumstances allow, to finish the closure process. By then, your family might not even want to go, but the plan to do so might help them now

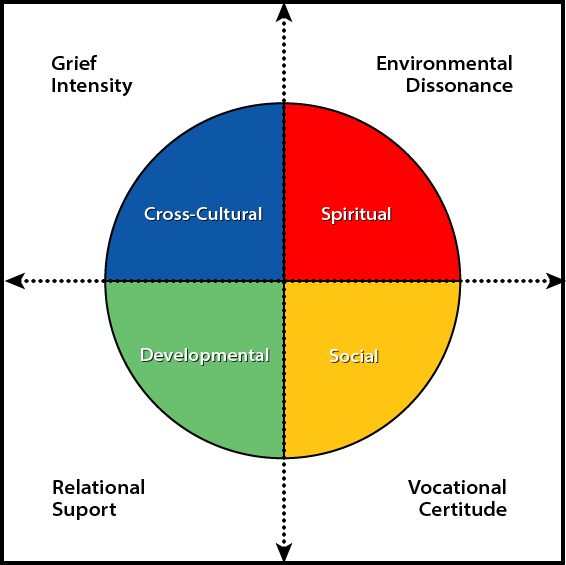

The Transition Challenge Matrix, developed by Michael Y. Pollock, is a very useful framework to understand the level of stress you and members of your family may experience upon re-entry, or any transition. Originally designed to help understand the issues faced by TCKs on re-entry, it is equally applicable to adult members of the family. Use this matrix to help you understand the level of stress you are encountering, and work on redressing the balance or reducing one of the stressors.

Four core dimensions that are in flux during re-entry are: Cross-cultural, Spiritual, Developmental, and Social (items inside the circle). These are adjustments that everyone has to make.

However, in addition, there are four other factors that affect the re-entry process: Grief Intensity, Relational Support, Environmental Dissonance, and Vocational Certitude. These factors have a sliding scale of intensity, depending on personal experience.

For example, if Margaret is experiencing intense grief and environmental dissonance because Washington, DC is so different from Kampala, Uganda, and has little relational support from her parents as they are still overseas, her re-entry stress will be high stress. Conversely, if John returns with his family to DC, and his best friend’s family has recently relocated back to DC too, his re-entry shock will be less than Margaret’s.